Friday, April 2, 2010

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

The Big Wind, Hurricane of 1938

This post is material I submitted to Milford Magazine, Fall 2009 issue, with some original photographs never before published. See more by looking up the fall issue, page 38, for the hurricane of '38.

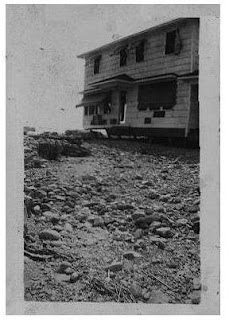

This post is material I submitted to Milford Magazine, Fall 2009 issue, with some original photographs never before published. See more by looking up the fall issue, page 38, for the hurricane of '38. Cherry Street and Darina Place several days after the blow. Immediately after the storm you could walk from Gulf Street to Prospect Street on the downed trees without ever touching the ground.

Cherry Street and Darina Place several days after the blow. Immediately after the storm you could walk from Gulf Street to Prospect Street on the downed trees without ever touching the ground. The storm surge was so great the Old Gulf Street Bridge, now used for pedestrians and fishing, was ripped from its moorings and the water main line was left dangling. Very few sewers existed in 1938. Look under the bridge to see at the low tide how river bottom itself was ripped up by the surge.

The storm surge was so great the Old Gulf Street Bridge, now used for pedestrians and fishing, was ripped from its moorings and the water main line was left dangling. Very few sewers existed in 1938. Look under the bridge to see at the low tide how river bottom itself was ripped up by the surge.Bay view was still mostly empty a block away from the shore. Most of the ranch style cottages there were built after the war (WWII) The shorefront homes on the west side on and near Lawrence Ave., took a beating.

The Big Wind

September 21 started as a quiet late summer day, the first day of Autumn. The day was warm and sunny. People went to work, Children were sent off to school. Everything was normal. Some noted that all afternoon the skies darkened and the wind picked up.

In Late August a tropical whirlwind spun off the African coast for a run across the Atlantic. It crossed he Ocean at Latitude 15oN then in mid-ocean began to swing North. The storm, now a hurricane, passed well north of the Caribbean and the Bahamas then swung due north to slip between Cape Hatteras and Bermuda in an arc that a hundred times before and since would have taken her to the hurricane graveyard of the cold north central Atlantic. By September 19th its path was so typical the then marginally efficient US Weather Service dropped any concern for it . The unnamed storm appeared to be of no danger.

A not so funny thing happened to it on its projected route to oblivion, the storm veered from its parabolic path, strengthened and turned due North. It ran parallel to the coast at a speed two to four times faster than any wireless equipped ship in its path. The coast of Long Island and New England would be as without warning as any storm since the also “unforeseeable” Hurricane that destroyed Galveston 38 years earlier.

The storm lashed Long Island. Most homes on eastern Fire Island were just gone, their debris tossed into the bay behind. In the Hamptons, on the “Strong side,” it was so bad that the instruments of the weather observatory were destroyed even before the storm crested. No word had been spread. Phone and telegraph lines were down, wireless towers twisted like pretzels.

The “Long Island Express” as it also came to be known, roared across Long Island at 50 miles per hour. In just 20 minutes it would slam into Connecticut. In downtown Milford nobody took it seriously. Maybe it was just a strong afternoon thunderstorm like dozens each summer. The previous four days had been nothing but rain. Dark and dreary was not unusual in the Northeast.

Teachers let their children out of school at the normal time. Most walked or took the trolley to all corners of Milford as the wind howled in a swirling dark sky. Near today’s Silver Sands State Park, waves broke and the spray flew over the open, “summer style,” tram motoring on East Broadway.

At 3:30 p.m. the eye nearly 30 miles wide made landfall east of New Haven covering the east shore all the way to Saybrook. The advancing right or strong side of the hurricane killed upwards of 700 and wiped clean coastal communities as though by a giant arm. Damage costs exceeded even the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

With the season over, most of the shore was boarded up and deserted. Had the Storm struck in August, thousands more could have died, likely killing many in Milford. Most beachfront homes lacked foundations and seawalls. Summer homes were lifted to their destruction as the surge raced through their pilings.

Inland most of the damage was caused by hundreds of falling trees. One could walk along Cherry Street from Gulf to Prospect Streets without ever stepping on the ground. It took weeks to restore the utility lines and clear all the debris. The Storm did provide unexpected clean-up work for a lot of people during the depression.

After crashing into the Coast, the greatest New England storm ever caused massive flooding to the North before moving over Lake Champlain to die in Western Ontario. No major storm since has taken the same path, at least YET.

Joseph B. Barnes, Esq. © 2009